The sheer scope of laws and regulations covering contracts with the US Federal government is where government contracting fundamentally differs from commercial contracting. How well you manage government contract compliance can either make you a favored government provider, or land you hefty financial penalties, blacklisting – and even prison time.

And it can be resource-intensive. In fact, whether a Federal agency has the bandwidth to conduct the appropriate regulatory scrutiny is one of the factors that can determine which contract type they choose for a project.

So let’s delve into this world. The depth of the topic would fill a book, but we’ll get a solid overview of the major components.

We’ll focus on the Executive branch because its reach and influence means that other branches and levels of government often use or adapt its regulations, so reviewing Executive contracting-related regulations will give you a good foundation if you want to work with, say, the Legislative branch or a State government.

Table of Contents

Contracting Regulations

The Executive branch is, of course, vast. Acquisitions.gov has regulations for 30+ agencies! And the GSA has its own policies and regulations. Thankfully, the bulk of all that is based on the Federal Acquisition Regulation. All contracts with the Executive branch must comply with FAR.

FAR

The GSA (General Services Administration) defines FAR as “the primary regulation for use by all executive agencies in their acquisition of supplies and services with appropriated funds.” It is issued jointly by the GSA, DoD, and NASA, and includes standard elements of bid solicitations and contracts, as well as a number of FAR supplements for individual agencies. FAR explains in detail (53 parts), for both agencies and contractors, how the federal acquisition/procurement process works from pre-solicitation to sustainment. It also provides the exact legal clause language that is added to applicable contracts, so you can prepare even if you’ve never see such a contract.

To illustrate how comprehensive FAR is, there are parts dedicated to:

- Application of Labor Laws to Government Acquisitions (Part 22)

- Protection of Privacy and Freedom of Information (Part 24)

- Patent Rights under Government Contracts (Part 27)

- Acquisition of Information Technology (Part 39)

Because FAR sets the standard for government contract compliance in all Executive branch agencies, most agencies only need to note where their acquisition requirements differ from FAR’s. The most notable of these Supplements is DFARS, the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement, which covers the DoD’s requirements. Note that the Marine Corp, Army, Navy, and Air Force have their own additional Regulation Supplements.

One section in DFARS deserves special attention: 252.204-7012 (Safeguarding Covered Defense Information and Cyber Incident Reporting) specifies additional requirements for Defense contracts. These include minimum security protections for information and cyber-incident reporting/response requirements.

CAS

CAS is the Cost Accounting Standards. The larger the award amount for a negotiated contract, the greater the chance for errors and fraud, so contracts with awards above certain amounts come with special accounting standards. CAS was created, as the name indicates, to enforce consistency in cost accounting practices. There are 19 standards, covering everything from home office expenses to tangible assets to compensated personal absences to pension costs, and much more.

CAS tells you not only what cost accounting practices are required, but how to achieve them in a satisfactory way. CAS is defined in Title 41 in the U.S. Code and Title 48 Chapter 99 of federal regulations, and is referred to in various places; FAR Part 30 prescribes how CAS contracts are to be administered.

Special clauses should be present in every contract that requires CAS compliance, but of course you’re ultimately responsible for knowing which CAS standards apply and complying with them. CAS requirements include your cost accounting system, documenting the cost information used, and cost accounting at every stage in the contract lifecycle.

What does CAS apply to?

Unlike FAR, CAS only applies to cost accounting rather than the entire procurement process, and only to negotiated contracts above $7.5 million. There are a number of exemptions – including whole categories like sealed bids and commercial contracts. There are also two types of CAS coverage that might apply to you, based on the sum of the CAS-covered contracts you have during a particular cost accounting period:

| Coverage | Applies To Business Units If… | Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Full | They receive a single CAS-covered contract award of $50+ million, or received that amount in awards during their previous cost accounting period. | Comply with all of the CAS specified in part 9904 that are in effect on the date of the contract award, and with any CAS that become applicable because of later award of a CAS-covered contract. |

| Modified | They receive a covered contract under $50 million, and received under $50 million in net covered awards in the previous cost accounting period. | Comply with these Standards: 9904.401 (Consistency in Estimating, Accumulating, and Reporting Costs); 9904.402 (Consistency in Allocating Costs Incurred for the Same Purpose); 9904.405 (Accounting for Unallowable Costs); 9904.406 (Cost Accounting Standard—Cost Accounting Period) |

CAS also requires you to submit a Disclosure Statement as part of your proposal, unless you already have one on file AND the new contract – if awarded to you – wouldn’t require an update to it. A Disclosure Statement is a form disclosing your cost accounting practices, policies, and procedures. A clause in the contract will tell you what you need to do.

TINA

TINA stands for Truth in Negotiations Act, originally passed in 1962. That Act has been renamed “Truthful Cost or Pricing Data,” but it’s still often referred to as TINA (easier to say than TCPD). TINA helps prevent fraud and shoddy bidding by verifying that the proposed costs and prices used for a bid are consistent with the actual costs and prices – so that, for instance, if your subcontractor costs or labor expenses change substantially, the contract is properly amended. The goal is to ensure fair and reasonable contract pricing.

TINA compliance for government contracting means that an agency must evaluate all initial contracts within a certain award range, and all cost/price changes to existing contracts, against TINA’s criteria. These criteria determine whether or not you’ll be required to submit a signed certificate stating that the cost or pricing data you’re providing are accurate, complete, and current. Since competitive bidding generally produces fair and reasonable prices, TINA focuses mostly on solo bids; the definition of “adequate price competition” does leave room for some solo bids to be excluded from the requirements.

Which contracts does TINA apply to?

There are two monetary thresholds that govern TINA: the “simplified acquisition threshold” and the trigger threshold. Both amounts are adjusted every five years; as of October 1, 2025, they are $350,000 and $2.5M respectively. With some exceptions, certified cost and pricing data is only required for contract awards above the trigger threshold. Exceptions include when:

- Adequate price competition exists

- The prices that apply to the contract are set by law or regulation

- The contract is for commercial products or services (as defined by TINA)

- A waiver is granted because the agency can determine on their own, without needing certified data from you, that the price is fair and reasonable (if, for example, this contract is close enough to a previous buy)

In addition, even if the award amount is below the trigger threshold, an agency can require a certificate as long as the amount is above the simplified acquisition threshold – and as long as they provide a justification.

The way TINA applies to pricing changes over the contract’s lifecycle needs some explanation. With some exceptions, price adjustments up and down both count equally; it’s the amount of the change, not the direction, that TINA cares about. For example, an adjustment of -$500K followed by an adjustment of +$750K are treated as a total price adjustment of $1.25M, even though the net change is only +$250K.

As price adjustments accumulate, if the total price adjustment at any point exceeds the trigger threshold, then you’ll have to submit certified cost and pricing data BEFORE the contract can be amended. Note that this can happen even when the net total contract amount stays above the trigger threshold – if, for example, a $6M contract goes through several downward adjustments totaling $2.6M.

What counts as cost or pricing data?

Generally speaking, it covers all facts that a reasonable person would expect to significantly impact price negotiations. This can include:

- Vendor quotations

- Nonrecurring costs

- Information on changes in production methods and in production or purchasing volume

- Data supporting projections of business prospects and objectives and related operations costs

- Unit-cost trends such as those associated with labor efficiency

- Make-or-buy decisions

- Estimated resources to attain business goals

- Information on management decisions that could have a significant bearing on costs

What does it mean to submit certified cost or pricing data?

When you’re required to submit certified data, that means you send your CO (agency Contracting Officer) the data itself, along with a Certificate of Current Cost or Pricing Data certifying that to the best of your knowledge and belief, the submitted cost or pricing data are accurate, complete, and current. FAR provides a template for the certificate.

Note that the CO may require additional cost or pricing data beyond the certified data, if it’s needed to determine that the price is fair and reasonable.

Protected Data Categories

The regulations that govern bidding on and working contracts tend to get most of the attention in discussions of government contract compliance, but you also have to comply with applicable data storage and transmission regulations. Your contract should make clear what regulations apply, but as always, having your own understanding what’s required is the best policy.

The key factors that dictate how government information must be managed are: whether or not it’s classified, and what sort of controls must be maintained on its storage and dissemination. Classified means you need special clearance (Confidential, Secret, Top Secret) just to see it; Unclassified means you don’t. Unclassified material is often subject to controls, whether it’s to limit what people are allowed access, where it can be stored or transmitted, how secure it has to be while being stored or transmitted, whether (or where) it can be exported, and so on.

There are subcategories of Classified, but the world of Unclassified-yet-protected categories is much broader and varied, so let’s look at the categories of protected Unclassified information you’re most likely to encounter.

CUI

CUI stands for Controlled Unclassified Information.

What is it?

It is a broad designation that was created to consolidate what was once an array of designations for unclassified information, like SBU and FOUO. The CUI program was established by Executive Order, and is laid out in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 32, Part 2002. Since Congress has never passed a standard version of it, each agency has been responsible for implementing it for themselves.

What counts as CUI?

The official definition is, “All unclassified information throughout the executive branch that requires any safeguarding or dissemination control is CUI.” CUI includes an array of subcategories, and is defined somewhat differently by different agencies, but they all include rules for safeguarding, accessing, disseminating, decontrolling, and marking CUI material. A CUI designation also triggers special protections defined in CMMC and NIST SP 800, which we’ll cover later.

What do I have to do?

Contractors are required to protect CUI whether it’s on paper or in computer systems, by following the rules for handling the material throughout its lifecycle. This includes who has access, how the material is stored, who it can be shared with and how, what to do with the material when government controls are removed, how to mark it as controlled, and a lot more. These rules apply to everyone who has access to the material, regardless of their role or relationship to the agency or contractor. Note that some agencies, like the DoD, require annual CUI training.

There are three varieties of CUI: Basic, Special, and a Basic/Special hybrid. The difference lies in whether the government provides no, some, or complete specific controls for the material.

- CUI Basic requires you to protect and control the material according to the standard specifications laid out in the CUI regulations and in the relevant entries in the CUI Registry (a list of regulations applying to specific areas of information).

- CUI Special provides additional instructions that differ from and supersede CUI Basic.

- The hybrid variety is a subset of CUI Special where some additional instructions are provided but not a full set, meaning that CUI Basic controls apply to the rest.

There are also agency-specific variants of CUI, like the DoD’s CDI (Covered Defense Information), which is defined in DFARS.

What are “Limited Dissemination Controls”?

The CUI program recognizes that the federal government’s impulse is often to over-protect information. Its General Dissemination Principles make sharing information the default that has to specifically be overridden. If an agency believes that certain material needs to be controlled beyond the methods provided by the CUI program, they can use Limited Dissemination Controls to do so.

These controls let the agency restrict sharing based on factors like, for instance, “no foreign nationals” (NOFORN – note that NOFORN applies to anyone you work with who could have access to the material), “federal employees and contractors only” (FEDCON), and “Attorney-client.”

Legacy designations replaced by CUI

Since the CUI program has to be implemented by each agency – and since even after an agency does so, it has all its previously-categorized Unclassified material – you may still encounter legacy designations. Two common ones are SBU (Sensitive But Unclassified) and FOUO (For Official Use Only). Like CUI, they don’t contain national security information, so they can’t be Classified, but they still need protection against inappropriate access and disclosure for other reasons.

SBU material might include personal information about individuals, confidential business information, law enforcement information, privileged attorney-client communications, and federal tax information. The same types of protection required for CUI apply to SBU, but the details vary even more because each agency decides what to designate as SBU. For example, section 10.5.8 of the IRS’s manual lays out that agency’s policy for protecting SBU.

Agencies have different policies and practices for designating FOUO. The DoD, for instance, uses it for information that “may be exempt from mandatory disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).” The details vary by agency, but common restrictions include: it can’t be discarded in the open trash, made available to the general public, or posted on an uncontrolled website.

FCI

FCI stands for Federal Contract Information.

What is it?

FCI provides basic security controls for a wider array of less sensitive information than CUI.

What does it apply to?

FAR 52.204-21 defines FCI as, “information, not intended for public release, that is provided by or generated for the Government under a contract to develop or deliver a product or service to the Government, but not including information provided by the Government to the public (such as on public websites) or simple transactional information, such as necessary to process payments.”

In short, FCI is all the information generated over the lifecycle of a federal contract. Consider email. Working with the federal government means lots of emails. You have to consider who has access to those emails at every step of their existence. You have to protect them during transmission, storage, and backup, for every device used to access those emails. Any printouts of those emails must also be protected. And so on.

What do I have to do?

FAR lists a set of 15 security controls for information systems owned or operated by a contractor who processes, stores, or transmits FCI. They represent the minimum you must do to protect FCI, and cover components like identity verification for access to information systems and physical spaces, system connections, visitor monitoring, and malicious code protections. Note that any system with CUI-compliant security controls adequately protects FCI.

General Data Protection Laws and Regulations

With an understanding of the categories of protected Unclassified material you’re most likely to encounter in government contract compliance, we can turn to the major laws and regulations in place to protect that material.

FISMA

FISMA is the Federal Information Security Management Act, Title III of the E-Government Act of 2002, passed by Congress; it was updated in 2014.

What is it?

It aims to “provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of information security controls over information resources that support Federal operations and assets … provide for development and maintenance of minimum controls required to protect Federal information and information systems; provide a mechanism for improved oversight of Federal agency information security programs.”

By providing directives – to federal agency heads, NIST (see below), and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) – to strengthen information security systems, FISMA laid the groundwork for much of the regulation discussed in sections below. It takes a risk-centric approach.

What does it apply to?

According to NIST, FISMA applies to “Federal agencies, contractors, or other sources that provide information security for the information and information systems that support the operations and assets of the agency.”

What do I have to do?

FIPS 199 and 200, and NIST SP 800-53, were developed to provide the details mandated by FISMA. We’ll discuss them next. To support implementation of risk management programs to meet FISMA’s requirements, NIST has also published a Risk Management Framework that provides a seven-step process and links to a suite of NIST standards and guidelines.

FIPS

FIPS is the Federal Information Processing Standard.

What is it?

NIST’s Information Technology Laboratory (see below) develops FIPS publications for federal agencies, but they are often developed from standards established by technical communities in the private sector, like ANSI, IEEE, and ISO – and are also often used by the private sector.

What does it apply to?

FIPS publications provide standards for protecting non-national security information in federal systems, when NIST determines that there are no existing voluntary consensus standards it believes would adequately provide the required protection. There is no general applicability for all publications – each one has an applicability section that indicates whether that publication is mandatory for federal agency use.

There are currently 13 publications, mostly covering specific cryptography-related topics. 199 and 200, however, apply to all federal information and information systems, so you should familiarize yourself with them. They were mandated by FISMA.

FIPS 199 defines standard Security Objectives (the level of concern for confidentiality, integrity, and availability) and Impact Level (potential impact in the event of unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction) that agencies must use to categorize their information and information systems; these are also referred to in other data protection regulations. It illustrates how to map Security Objectives and Impact Levels onto information systems and types of information. Since agencies are required to apply these categories, you must also apply them to any federal information and information systems relevant to your contracts.

FIPS 200 builds on 199 by specifying minimum security requirements for seventeen categories of information and information systems, using the definitions in FIPS 199. These requirements must be met by selecting the appropriate security controls and assurance requirements for those categories as described in NIST SP 800-53.

NIST SP 800

NIST is the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

What is it?

- NIST is an agency within the Dept. of Commerce best known for the specifications and measurement standards it defines for a wide range of industry, academia, government, and other users. It also operates laboratories, conducts research, establishes guidelines, and even performs technical investigations.

- SP stands for Special Publication, which NIST has issued to develop information security standards and guidelines.

- The 800 series has been developed to address and support the security and privacy needs of federal information and information systems.

There are two publications in SP 800 that are vital for government contract compliance. The first one establishes a broad set of security and privacy controls for federal information systems, with an eye to protection from threats and risks. The second is a modified subset of the first, focused on CUI protection for components of nonfederal information systems that process, store, or transmit CUI or that provide protection for such components.

What do I have to do?

There are 20 “families” of requirements in 800-53, and 17 in 800-171 – covering everything from Access Control to Incident Response to Maintenance to Planning, and beyond – with over 100 total requirements. Common themes include:

- Thoroughness – e.g., if you give even one person access to more information than they need access to, you risk that information.

- Monitoring – if you don’t know *everything* that happening with the CUI information in your systems, you risk that information.

- Compartmentalization – more barriers are better than fewer. A physical analogy would be: just because someone has access to your driveway doesn’t mean they should have access to your front yard, or access to your front door, or access to the space right inside your front door, or access to a hallway/staircase, and so on.

Since 800-53 applies to federal systems, the level of detail, rigor, assessment, and monitoring required is generally higher than for 800-171.

SP 800-53

Titled “Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations,” SP 800-53 describes itself as “a catalog of security and privacy controls for information systems and organizations to protect organizational operations and assets, individuals, other organizations, and the Nation from a diverse set of threats and risks, including hostile attacks, human errors, natural disasters, structural failures, foreign intelligence entities, and privacy risks.”

What does it apply to?

All federal systems and those who interact with them – including contractors. If the contract would involve access to or operation of a federal system, it should specify compliance with SP 800-53.

SP 800-171

Titled “Protecting Controlled Unclassified Information in Nonfederal Systems and Organizations,” SP 800-171 supplements requirements specified in the CUI Registry, and applies to components of nonfederal systems that process, store, or transmit CUI, or that provide protection for those components. As the SP states, “The responsibility of federal agencies to protect CUI does not change when such information is shared with nonfederal organizations. Therefore, a similar level of protection is needed when CUI is processed, stored, or transmitted by nonfederal organizations using nonfederal systems.”

What does it apply to?

Any contract that involves CUI material. Note that SP 800-171 augments rather than replacing SP 800-53, so some contracts will require compliance with both.

Cloud Data Protection Laws and Regulations

Cloud data and systems are much more exposed to risk than on-prem data and systems, and require more effort to protect. Here are the major regulations and programs governing that protection.

CMMC

CMMC stands for Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification.

What is it?

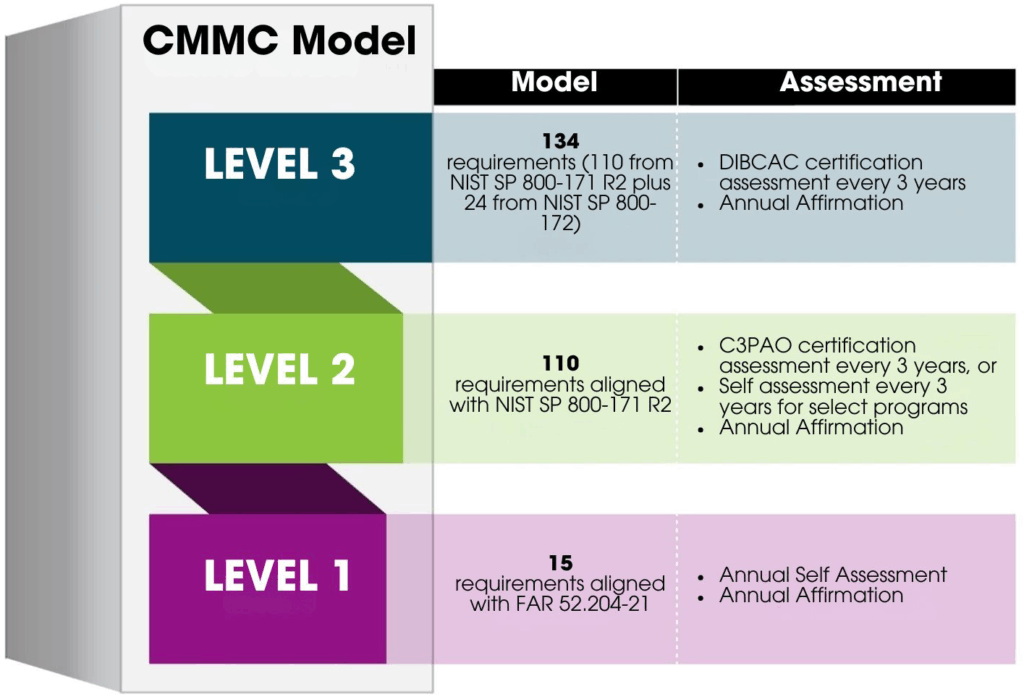

CMMC is a framework developed by the DoD to protect the defense industrial base from “increasingly frequent and complex cyber attacks” by enforcing protections on CUI and FCI material in contractors’ systems. It features three levels of increasing protection for increasingly sensitive information, with certification for CUI being handled by a third party. Here is a graphic straight from the DoD to explain the differences between Levels 1, 2, and 3.

What does it apply to?

FCI and CUI material related to contracts with the DoD. Level 1 applies to FCI. Levels 2 and 3 apply increasing levels of security to CUI material.

What do I have to do?

That will depend (see note below) on the level of CMMC certification required for the contract in question, but the short answer is: compliance assessment and affirmation. You must be certified compliant with the applicable CMMC level as a condition of the contract award. The first step is assessing whether you’re compliant with the applicable requirements, which may be self-assessment or assessment by either a Third Party Assessment Organization (3PAO) or by the Defense Industrial Base Cybersecurity Assessment Center. The second step is providing an annual affirmation verifying compliance with the applicable requirements.

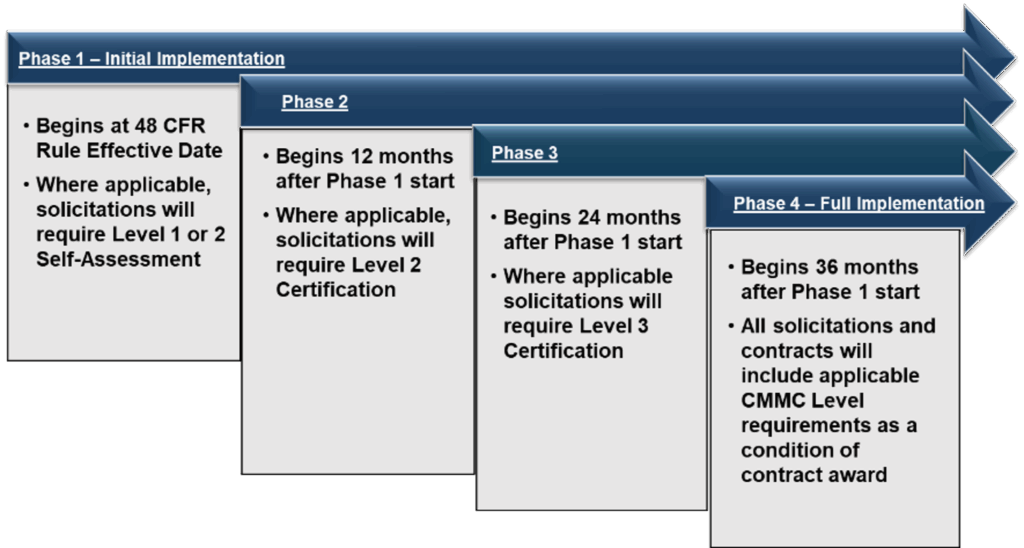

Note: CMMC is new enough that its implementation is only now beginning (Fall 2025). CMMC assessment requirements will be implemented using a four-phase plan over three years, with self-assessments being required from the start, and certifications being added in subsequent years. So it’s vital to understand what phase you’re in.

FedRAMP

FedRAMP is the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program.

What is it?

As part of the larger effort to protect information per NIST SP 800-53, FedRAMP standardizes security assessment methodology, authorization, and continuous monitoring for cloud products and services. Cloud offerings require extra consideration and protection because they present extra risk. By officially authorizing a set of cloud providers, FedRAMP provides agencies confidence that the provider they choose meets high security standards and complies with federal regulations. The Cloud Service Provider Authorization Playbook describes the following in detail.

Impact Levels

Every cloud offering you want FedRAMP authorization for will fall into one of three Impact Levels (defined in FIPS 199): Low, Moderate, and High. The difference comes down to whether, if your cloud offering were to lose confidentiality, integrity, or availability, the result would be limited, serious, or severe/catastrophic adverse effects on a federal agency’s operations, assets, or individuals. Each Level comes with a required set of security controls. Assessing which Impact Level applies to your offering will help you design your strategy for FedRAMP authorization.

The Marketplace

FedRAMP provides a Marketplace where agencies can find an authorized product or service. The Marketplace designates an offering as FedRAMP Ready, FedRAMP In Process, or FedRAMP Authorized. Authorized is when your offering can be selected and used by agencies. In Process is the first required designation; Ready is an option designation that Moderate and High Impact Level cloud offerings qualify for. You can achieve FedRAMP Ready before you have established a relationship with an agency, and it gets your offering listed in the Marketplace.

Why is this useful? Agencies have to plan ahead, so if they like your offering, they can start planning for when it achieves Authorization. Ready can also be useful if you don’t plan to list in the Marketplace, because it’ll help you identify any gaps in your cloud offering’s security before you’ve started the much more involved second and third steps.

What does it apply to?

Any cloud products or services (PaaS, Iaas, Saas, etc.) that create, collect, process, store, or maintain federal information on behalf of federal agencies must be FedRAMP authorized. The one exception is private cloud deployments intended for single organizations and implemented fully within federal facilities; see NIST SP 800-145 for applicable definitions of cloud deployment models.

What do I have to do?

If your offering qualifies for the optional FedRAMP Ready designation, you need to work with a Third-Party Assessment Organization (3PAO) to complete a Readiness Assessment Report that documents your capability to meet federal security requirements. You can do that before you’ve established a relationship with an agency, but you’ll need one to get any further. FedRAMP compliance for government contracting involves three phases:

- Pre-Authorization: The goal of the Pre-Authorization phase is to formalize your relationship with an agency and get them up to speed on your offering, including its functionality, project status, and security requirements. When that’s done, your Marketplace listing becomes FedRAMP In Process.

- Full Security Assessment: Achieving FedRAMP Authorized is a thorough two-step process: Full Security Assessment, then Agency Authorization. It must all take place within a year from reaching In Process. During the Full Security Assessment, the 3PAO tests your cloud offering according to the FedRAMP guidelines and requirements, and reports its findings. You then create a plan to address to those findings, and both the 3PAO and you present to the agency.

- The Agency Authorization Process is the last phase. In it, the agency reviews the package of material that you and the 3PAO presented, and may conduct its own testing of your offering’s security controls. You may be required to remediate flaws identified in your offering. The last step the agency takes is to perform a risk analysis before issuing an Authority to Operate letter for your offering. FedRAMP then reviews everything to determine suitability for government-wide reuse and makes a FedRAMP authorization decision.

Once your cloud offering receives a FedRAMP Authorized designation, you will have to submit a monthly package of deliverables to ensure that the offering continues to meet the security requirements. For the same reason, a 3PAO will also complete an annual security assessment.

GovRAMP (StateRAMP)

What is it?

GovRAMP is a domestic nonprofit organization launched in January, 2021, to provide SLED (State, Local, and Education) organizations and contractors a simple standardized approach to cybersecurity verification and validation, based on FedRAMP. The program was called StateRAMP until February, 2025, when it rebranded. Built on NIST SP 800-53, GovRAMP recognizes that the Federal government isn’t the only organization that needs cybersecurity standards and verified solutions, and that it’s in everyone’s best interest to use FedRAMP as a base. If every one of the SLED organizations had to independently vet cloud services and products before using them, an enormous amount of time and money would be wasted, and the results would be inconsistent – risking the information in those organizations’ systems.

SLED officials, 3PAOs, and cloud service providers can join GovRAMP as members so they’re listed in the Member Directory. Service providers can also list their products in the Authorized Product List (APL), where SLED organizations can find them to use. There are five possible statuses a product can have in the APL. Note that since GovRAMP compliance is optional in many states, organizations don’t necessarily have to wait until your cloud offering achieves full authorization before using it.

- Core – Like FedRAMP Ready, this gets your cloud offering into the APL so organizations can begin considering it while you pursue authorization. It confirms implementation of 60 foundational NIST controls, and is assessed by the GovRAMP Project Management Office (PMO) without needing 3PAO assessment.

- Ready – Granted when a 3PAO and the PMO have verified that your cloud offering meets the minimum mandatory requirements and most critical controls, and that all outstanding issues or inquiries have been resolved. GovRAMP Ready indicates a product is likely well positioned to comply with the full authorization requirements. No contract or government sponsor is required.

- Pending – Granted when you’ve completed a security documentation package, and your 3PAO has submitted a Security Assessment Report. Indicates that you’re just waiting for the PMO to review and verify your security package.

- GovRAMP Provisionally Authorized – May be used by a sponsoring organization to indicate that your security package passed most requirements but needs additional assessment to attain authorization.

- GovRAMP Authorized – Granted when an authorizing government official approves your security package, your 3PAO attests to your readiness, the PMO has verified that your product meets all of the mandatory requirements and critical controls, and all outstanding issues or inquiries have been resolved.

What does it apply to?

IaaS, PaaS, or SaaS solutions for SLED organizations that may process, transmit, and/or store data – including PII, PCI, and PHI.

What do I have to do?

The first step is to become a GovRAMP member. Then identify the appropriate security category required by the SLED organization (Low, Low+, or Moderate), and determine whether your cloud offering qualifies for the Fast Track (see below). You’ll need to select a GovRAMP-approved 3PAO, and work with them to assess your cloud offering and complete a package of documentation to submit to the PMO. There are also several fees to pay along the way. As with FedRAMP, once authorized, you need to submit required documentation for monthly, quarterly, and annual continuous monitoring reports.

What is the GovRAMP Fast Track?

If you have begun the FedRAMP authorization process for a cloud offering, or completed it, you can reuse your FedRAMP security package and 3PAO audit for GovRAMP authorization. This makes the process much faster.

DoD CC SRG

This is the Defense Department’s Cloud Computing Security Requirements Guide.

What is it?

The CC SRG lays out the necessary security controls and requirements for authorizing cloud-based solutions, whether the DoD is providing the solution themselves or using someone else’s. The DoD has been moving to use commercial and contractor cloud solutions instead of developing their own. Like GovRAMP, the authorization process builds on FedRAMP and NIST SP 800-53, and flows from the requirements of FISMA.

It’s updated regularly, in part because the technology changes so fast, and in part because the DoD continues to learn lessons from current authorizations. The authorization process is similar to FedRAMP, but with more involved parties plus more documentation, assessment, validation, and review. You can either reuse FedRAMP authorization and avoid a lengthy process, or work with a sponsor in the DoD for the full process. There are two kinds of authorization, ATO (Authorization to Operate) issued to a specific DoD entity for a cloud offering, and PA (Provisional Authorization) enabling entities across the DoD to use the cloud offering. The parties in the authorization process are:

- DoD Component – One of a number of organizational entities at the DoD who are authorized to issue an ATO to an MO, like the Navy, Army Corps of Engineers, DARPA, or the NSA. If you don’t reuse FedRAMP authorization, you must have a Component sponsor your cloud offering for DoD authorization.

- MO (Mission Owner) – People such as IT system/application owner/operators or program managers within the DoD Components, who are responsible for operating one or more information systems and applications. In other words, your customer.

- DISA (Defense Information Systems Agency) – various teams and roles fill the same basic purpose GovRAMP and FedRAMP do, ultimately issuing Provisional Authorization

- JVT (Joint Validation Team) – A group consisting of resources provided by the sponsoring Component, headed by a manager provided by DISA. They provide technical review and validation of various documentation you and the 3PAO submit.

- 3PAO – third party assessor organization, as we’ve seen previously

The DoD Cloud Authorization Services (DCAS) and DISA Storefront websites provide a list of cloud services with PAs, which Components can choose solutions from (like the FedRAMP Marketplace).

What does it apply to?

The CC SRG is intended for:

- Commercial and non-DoD federal cloud providers

- Components and MOs using, or considering the use of, commercial/non-DoD and DoD cloud computing services

You can download the current version, along with other related documents, from the DoD’s Cyber Exchange.

What do I have to do?

Due to the much higher security required for Defense contracts, the authorization process is much more complex, so we won’t get into it here. The general flow between the involved parties is: DISA –> JVT –> 3PAO –> JVT –> DISA –> MO; the DoD offers a public overview of the process.

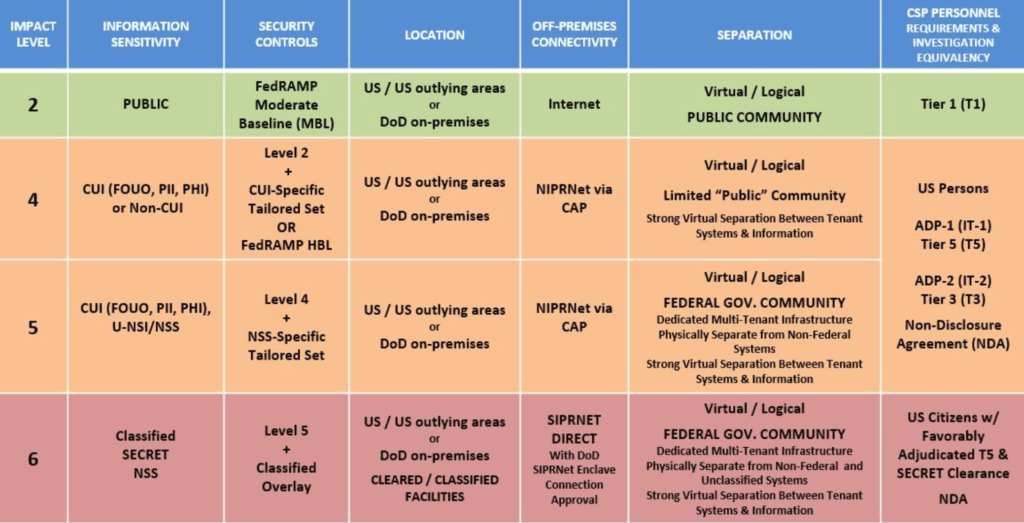

There are, of course, stricter security controls for more sensitive material. You need to know which Impact Level your cloud offering belongs in, which is assessed based on a combination of how sensitive the information is that your offering would handle, and the potential impact if a security event were to occur. Due to previous consolidation in the Impact Levels, there are currently four.

Here’s how they map onto various other factors.

Note that every time NIST SP 800-53 is updated to a new revision, the CC SRG is also updated, and you will need to take steps to achieve compliance with the new version.

Export Control Regulations

One of the key protections required for sensitive material is keeping it in the right hands (or eyes), and there are special requirements for material that’s restricted to certain people and organizations.

ITAR and EAR (see below) regulate export controls of certain items, and government contract compliance with both requires screened US Persons and data residency/sovereignty in CONUS. Using ITAR-compliant and EAR-compliant systems ensures that Foreign Persons won’t accidentally gain access to your data without the federal government’s authorization – as can happen, for instance, if a data center or customer service center is OCONUS.

Both sets of regulations use a pair of mutually exclusive phrases, “US Persons” and “Foreign Persons,” to designate who export activity is and is not allowed to.

| Category | US Person | Foreign Person |

|---|---|---|

| US citizen | Yes | No |

| Lawful permanent resident as defined by 8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(20) | Yes | No |

| Protected individual as defined by 8 U.S.C. 1324b(a)(3) | Yes | No |

| Any group, organization, or other entity doing business in the United States | Incorporated | Not incorporated |

| Any governmental (Federal, state, or local) entity | Yes | No |

| International organizations, foreign governments, and any agency or subdivision of foreign governments (e.g., diplomatic missions) | No | Yes |

At a high level, the goal is to strictly manage movement of restricted items from US to another country, and from the control of US Persons to Foreign Persons. “Movement” includes shipping, transmitting, transferring, and releasing (allowing visual, oral, or written access). “Items” include physical and digital products and services, as well as data about them.

Note that three types of activity count as “exporting” for ITAR and EAR purposes – we’ll use the term ‘export’ to cover all of them going forward:

- Export: includes movement out of the United States; movement within the US to a Foreign Person; and movement to a foreign embassy in the US (including agencies and subdivisions of an embassy).

- ITAR specifies that “any release in the United States of technical data to a Foreign Person is deemed to be an export to all countries in which the Foreign Person has held or holds citizenship or holds permanent residency.” EAR contains a similar provision.

- Reexport: includes movement from one foreign country to another foreign country; release or transference, in a foreign country, to a Foreign Person who’s a citizen or permanent resident of a different country; and transferring registration, control, or ownership of certain vessels, aircraft, satellites, and spacecraft between Foreign Persons.

- ITAR specifies that “any release in the United States of technical data to a Foreign Person is deemed to be an export to all countries in which the Foreign Person has held or holds citizenship or holds permanent residency.” EAR contains a similar provision, plus specifying that reexporting through a country counts as reexport to that country.

- (Re)Transfer: changing an item’s end use or end user within the same foreign country.

- ITAR includes temporary transfer to a third party within the same foreign country, as well as release within a foreign country to a Foreign Person who is a citizen or permanent resident of that country.

ITAR

ITAR stands for International Traffic in Arms Regulations.

What is it?

Part of the Arms Export Control Act of 1976, ITAR regulates the export of items (including technical data) produced for defense and military use. The word “export” in this context includes sharing information and material pertaining to technologies built for defense and military use – which is why you need to be familiar with it even if you’re not producing a physical product. The Department of State interprets and enforces ITAR.

What does it apply to?

ITAR applies to items, services, and data produced for defense use. The US Munitions List (USML) describes 21 categories of items subject to ITAR, such as various military vessels and weapons, along with their components (technical data is one). So any contract pertaining to the listed items will generate material that is also subject to ITAR.

What do I have to do?

Know whether a contract would include items on the USML. Know who among your employees, consultants, contractors, etc. – and those of any third party entities who may also have access to the relevant material (like call centers) – qualify as US Persons.

Before you can export any USML items (including, of course, information about them), you must register with the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls. You must then be authorized to actually export. This can take the form of a license, some other document of approval, one of several specific agreements, or an exception from needing one of the previous forms of authorization. Once you begin export activity, you must maintain strict security and movement controls to ensure that your export activity observes the limits of the authorization you received.

EAR

EAR stands for Export Administration Regulations.

What is it?

EAR regulates the export of US items that are not covered by the regulations of other federal agencies. The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), an agency of the Commerce Department, interprets and enforces EAR.

What does it apply to?

It applies to items, services, and data produced commercially that have defense or military uses. This is, of course, a much larger set of items than ITAR’s. For example, radar systems have broad use in commercial enterprises, but because they can also be a component in missiles (included in ITAR), their export is regulated by EAR. EAR applies to: all items currently in the US, all items originating in the US (no matter where they are now), all items made in foreign countries using US-origin components, and more. It makes exceptions for items whose export activity is regulated by other federal agencies, such as ITAR does, or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission – this ensures items aren’t covered by multiple export regulations.

Items subject to EAR fall into two categories: those listed in the Commerce Control List (CCL), and those not listed – which are referred to as EAR99. The CCL organizes every item into one of ten categories (like Materials Processing or Electronics), then one of five groups (like Software or Equipment and Components), and lastly one of nine Reasons for Control (like National Security or Missile Technology).

What do I have to do?

EAR compliance for government contracts means you have to determine certain key facts about your item: its official classification, destination, end user, end use, and conduct. Those facts dictate what you have to do for EAR, especially regarding the General Prohibitions (see below). Know whether your item is covered by the CCL, or by EAR99. Apply for a license or exception from BIS. EAR includes Steps for Using the EAR, which provides general guidelines, options, and steps for understanding and working your way through its process.

EAR contains a list of ten General Prohibitions, each of which describes export activity that requires either a license or a license exemption. BIS issues both licenses and exceptions. If General Prohibitions 4-10 don’t apply to an EAR99 item, then it doesn’t require a license.

You also have to observe the record-keeping requirements, which include official documents and correspondence, financial and accounting records, notes and memoranda, and more. EAR lists types of records whose retention is and is not required. And, of course, you have to follow the regulations governing the actual export activity itself, like an Electronic Export Information (EEI) filing for exporting tangible items.

Auditing and Other Monitoring

The factors that make strict oversight needed for the government contract pricing, bidding, and award process don’t just disappear once you have the contract. The more the award is for, and the more sensitive the project is, the more continual monitoring is required as you work to fulfill the contract. This ensures that taxpayer money is spent effectively and the agency gets what they pay for. So compliance for government contracting includes auditing.

A GAO report in April 2024, “Fraud Risk Management,” concluded that from 2018 to 2022, fraud cost the US federal government an estimated $233 billion to $521 billion annually.

Auditing for government contracts is much more rigorous and serious than it is for commercial contracts. Audits can take place at any time, and at multiple times, during the contract’s life cycle. Auditors may be suspicious of any irregularity or apparent case of noncompliance.

Audit agencies

There are entire agencies within federal departments that review, audit, and otherwise provide oversight on federal contracts. The General Services Administration, for instance, has the Office of Audits. The Interior Department has the Acquisition Audit Services Branch.

The DoD, of course, has its own audit agency, the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA). Its almost 5000 auditors work to ensure that contractors’ finances and financial systems follow applicable laws and regulations. Whichever federal department your contract is with, be sure you’re clear on its auditing requirements.

Defense contracts also come with oversight by the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), which provides start-to-finish contract administration services for more than 300,000 contracts. FAR lists more than 70 contract administration functions that DCMA fulfills. They cover virtually every aspect of a contractor’s business with the goal of ensuring that contractor supplies and services are delivered on time, at projected cost, and meet all performance requirements. Since small businesses have fewer resources, the DCMA may also evaluate your pricing and management systems before a contract is awarded.

Other sources of audits

In addition to audit agencies, departments and agencies at all levels of government may have an Office of the Inspector General, which conducts audits of programs and operations performed by contractors.

And then there’s the Government Accountability Office (GAO), whose core missions include determining whether federal funds are being spent efficiently and effectively, and how well government programs and policies are meeting their objectives. One of its teams is the Forensic Audits and Investigative Service. GAO provides a booklet for government contractors whose contracts are subject to GAO audit.

Audits, audits, everywhere! That’s how much scrutiny comes with government contract compliance. Note that lurking behind all these audits is CAS, which we met earlier.

The Takeway

On a basic level, compliance for government contracting boils down to two key questions:

- Are you properly handling the government’s data?

- Are you properly handling the government’s money?

The key to a watertight “Yes” on both questions is using cost estimation and proposal pricing software that’s built for government contract compliance. Your software can hold you back and get you in trouble – or it can turbocharge you.

Contact us today to learn how OAE helps you win more and scale faster.